What is a strandline? Debris that has been floating in the sea and rolling around on the seabed is pushed up the seashore by the incoming tide. This flotsam is left high and dry – stranded – when the tide goes out again.

The strandline marks the junction between the land and the sea. It is not a fixed point on the shore. There may be a succession of strandlines from lower to higher shore and running parallel to the water’s edge. The position of the strandlines depends on the high water level for each tide.

The height to which the tide will rise and fall changes with each tide. During any month the sea will move higher up the beach on successive tides for two weeks and then lower and lower after that until it is more or less back to the level it started at. The tides also vary throughout the year with several predictable very highs and lows. The weather will also affect the tides. Deep sea storms far away create great swells that hit the beaches even when the local weather is fair. Onshore winds may partially prevent the tide from going out and vice versa.

These movements bring lots of organic and inorganic debris ashore. For those of us who are not able to don wetsuits and scuba gear to look at the marine life under the waves, the objects found on the seashore, and the strandline in particular, are the only way to appreciate at first hand the wonderful variety of animals and plants that inhabit our coastal waters.

It is alway fascinating to discover what has been washed ashore at Studland Bay in Dorset. Until now in this blog I have mostly singled out interesting individual items to describe – such as seashells and seaweeds that I’ve found; but there is a much bigger picture of the strandline as a whole.

It’s exciting. You never know what you are going to find at Studland from one visit to the next. I love to make new discoveries. I am endlessly curious about what things are and how they got there. For the next couple of posts I am going to show some photographs of Studland strandlines taken in February, March, and April. I’ll highlight a few of the organisms that characterise each accumulation.

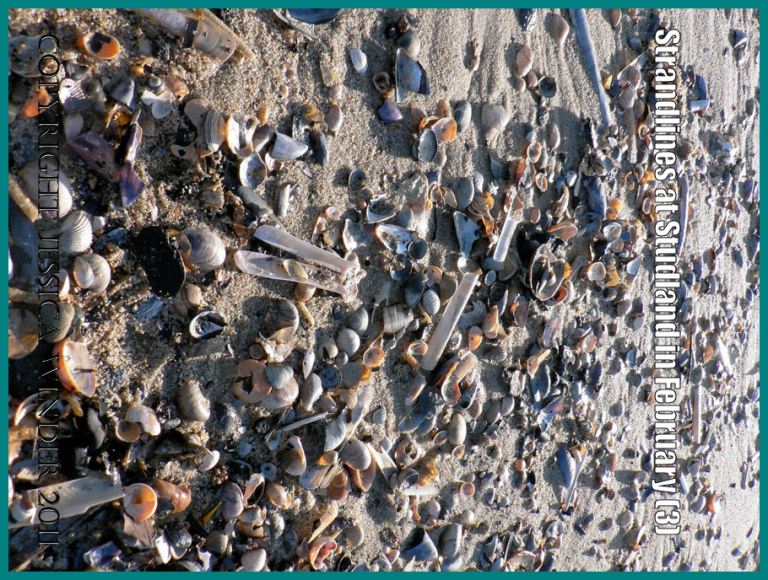

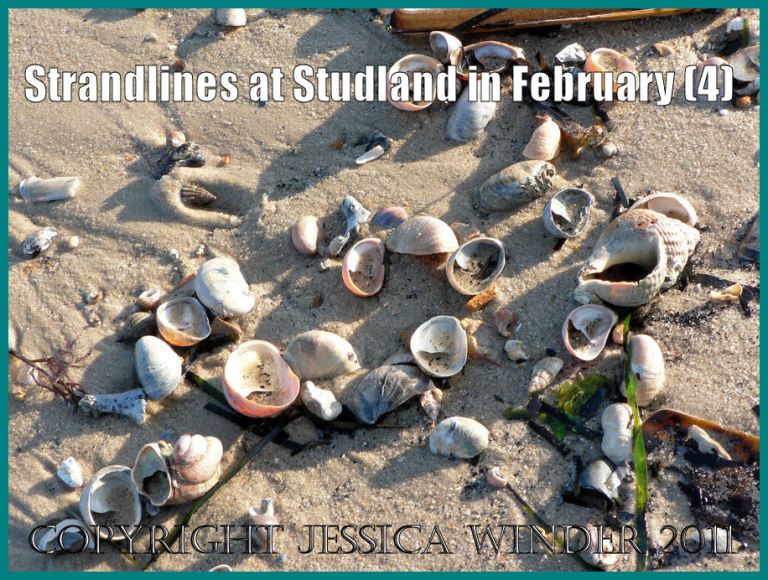

The photographs illustrating this post show what the fresh strandline looked like on one particular February day at Studland. Thousands of empty Slipper Limpet shells were the most dominant feature of the debris, with Razor Shells also being readily recognisable.

Here and there, groups of living Netted Dog Whelks scavanged amongst the debris for newly dead or dying shellfish on which to feed. They were especially common in the densest accumulations of the strandline and where the charcoal washes up.

Living Netted Dog Whelks prowled the strandline for prey.

Slipper Limpet and Razor shells dominated the strandline at this spot.

One living Netted Dog Whelk is ploughing its way through the wet sand in a characteristic fashion. The larger Common Whelk shell is a less frequent find on this beach.

At this point there were hundreds of tubes constructed from mucus and sand made by the Sand Mason and other marine worms.

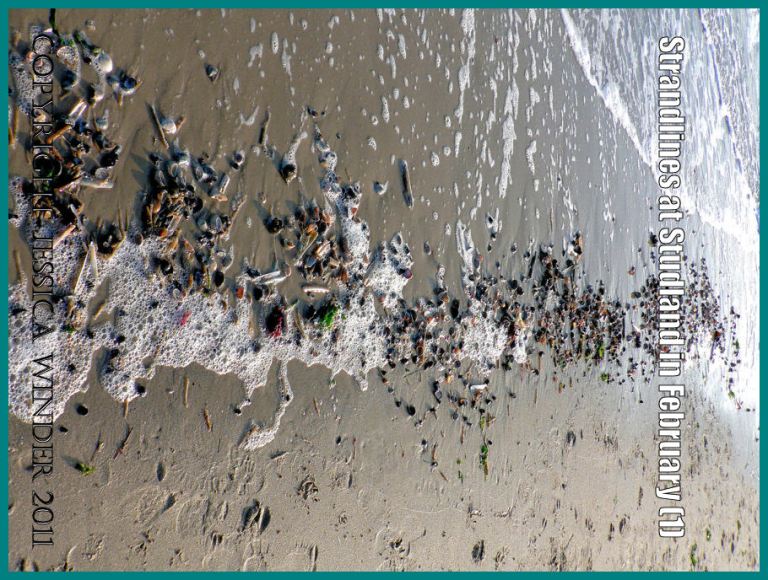

You can see how this strandline is actually in the process of being formed by the bubbles and foam left by the wave that has just retreated.

Revision of a post first published 7 June 2009

COPYRIGHT JESSICA WINDER 2011

All Rights Reserved

There’s something especially attractive in those places where the sea meets the sand. Strandlines can hold such wonders. Though the selection of shells look very similar to ours, the quantity of them on our beaches is much smaller.

LikeLike

Thank you, Amy-Lynn. I like nothing better than to sift through the strandlines for ‘treasures’. I expect the water in the English Channel is warmer, and the sediments more nutrient-enriched, than where you are. That might account for the greater abundance of shells at Studland.

LikeLike