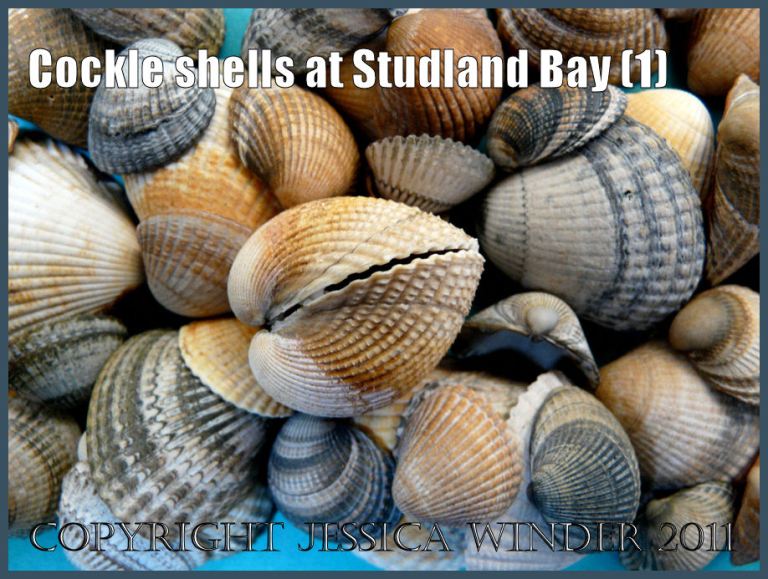

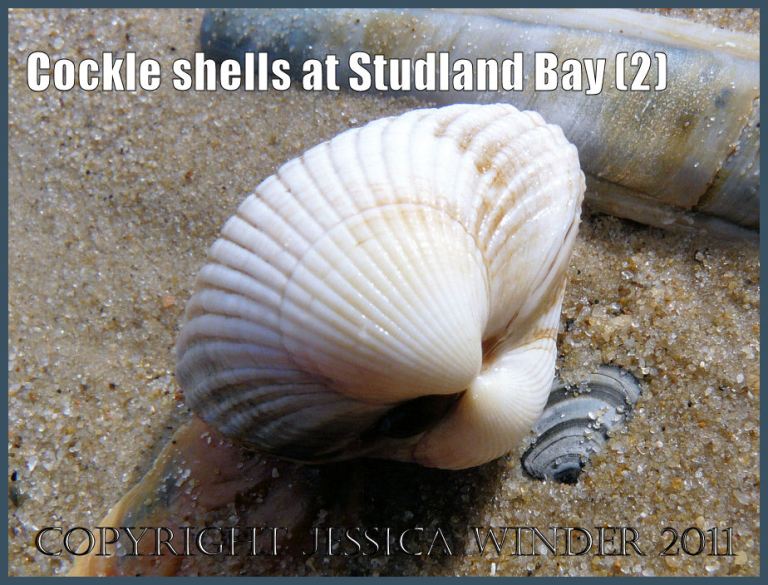

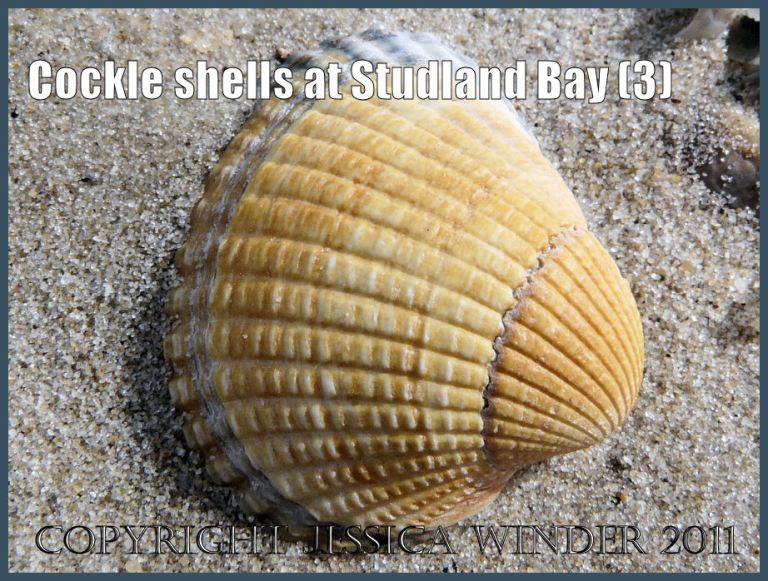

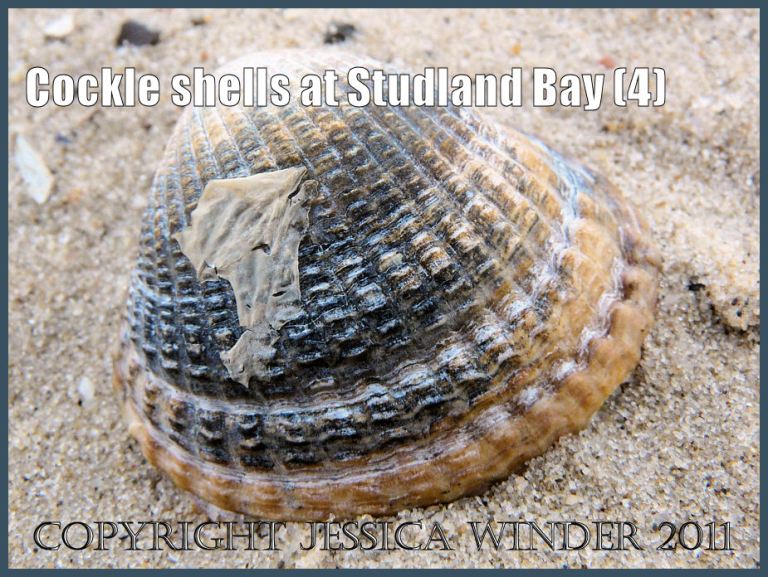

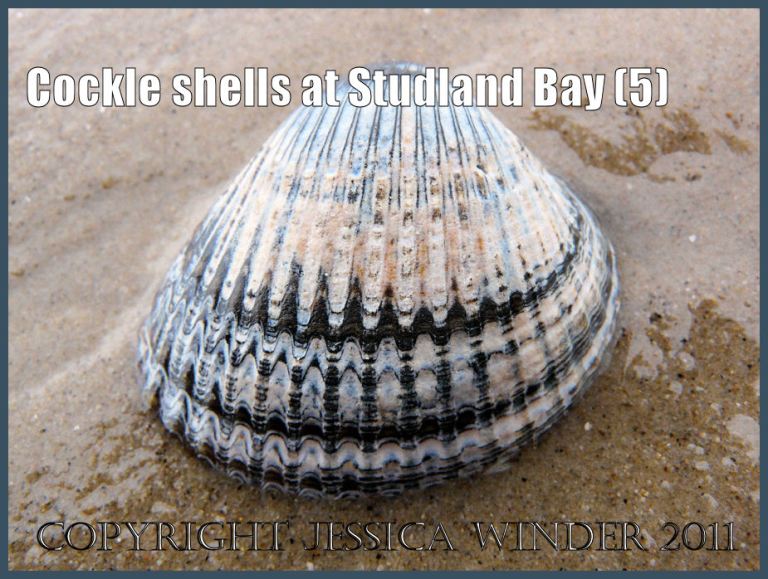

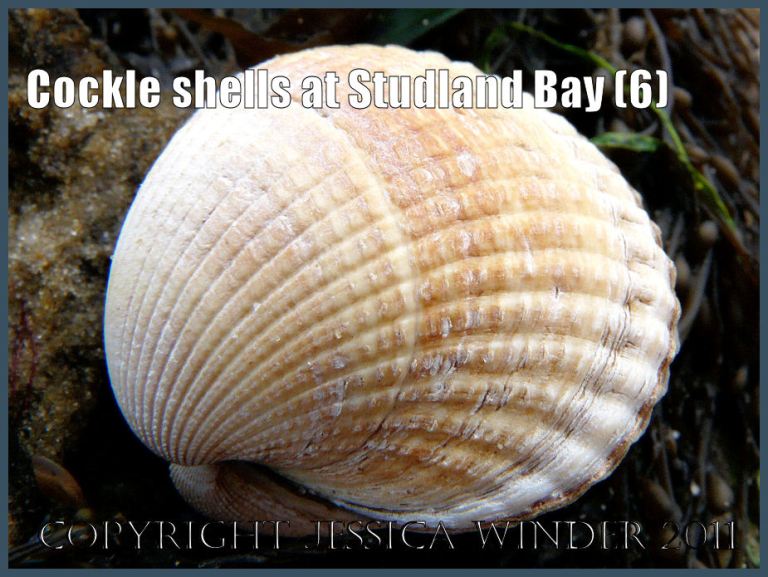

Empty cockle shells, multi-coloured, variably patterned, intricately sculptured, collected on Studland beach, can tell you quite a story. Common Edible Cockles, Cerastoderma edule (Linnaeus), have been a vital food resource since time immemorial. They have always been a relatively easy and abundant seafood to harvest. Nutritionally, the meats of these bivalved molluscs are full of goodness. They have been at various times a staple of the diet, and at other times something to fall back on when times were hard.

Poole has a particular association with cockles. To this day, cockles are fished – although in the 21st century this is by means of giant on-board pumps sucking them up from the seabed. In the not too distant past, cockles would have been raked from the muddy sands at low tide. This could have been done on a large scale by professional cockle fishers but also by individuals trying to eke out a living and provide for their own families.

Back in the 12th to 14th centuries, Milton Abbey owned land at Ower on the southern shores of Poole Harbour. Fish and other seafood was very important back then, especially in religious communities because it was the only ‘meat’ allowed on Fridays and Holy Days. The settlement near Ower Farm existed to exploit all the local marine resources and ship them back to the Abbey. Huge shell middens were excavated there when the Wytch Farm Oilfield was originally developed. There were many shells in these waste dumps, and a lot of them were cockles.

At first it was thought that they had been collected from the nearest stretch of shore in Newtown Bay. However, detailed study of the shells led to the discovery that the sediments would have been far too soft in that area to allow people to get out and fish for the cockles – on foot they would have sunk in the mud; and raking from boats was an impossibilty.

The size, shape, and number of ribs of the medieval cockle shells from Ower Farm were compared with modern samples from many locations in Poole Harbour, Poole Bay, the Solent and the Netherlands to find out where the ancient shells had came from. It was concluded that the cockles had probably grown on a small sandy islet located close to the inner harbour mouth where the cockle beds would have been exposed at low tides.

So one of the stories that empty cockle shells can tell is about our local history and how people lived in the past.

Click here for more posts and pictures of SEASHELLS in Jessica’s Nature Blog.

4 Replies to “Cockle shells at Studland Bay in spring”