Each tiny red-centred yellow petal in the flower-like pattern shown above is a small marine animal in a colony of the Star Sea Squirt, Botryllus schlosseri (Pallas). You can guage the size of these organisms from the white or transparent grains of sand scattered over the surface.

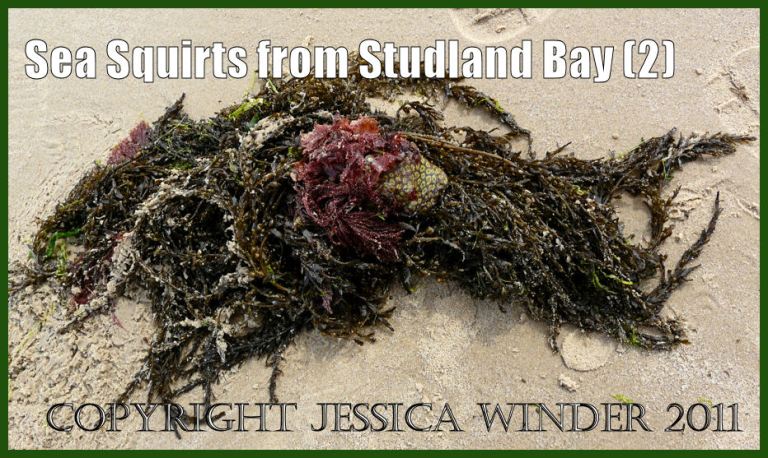

This colonial or group-living sea squirt was growing on the stem of some Japweed [Sargassum muticum (Yendo) Fensholt] that was washed up by the sea onto the sandy shore of Studland Bay in April. Red seaweeds were also growing on the stem.

In this closer view you can see that the colony of Star Sea Squirts was quite substantial and formed fleshy lobes – looking a bit like a decorated and blunt-tentacled sea creature.

Although this organism is said to be common, the only other time I have seen Star Sea Squirts on the seashore was at Ringstead Bay on some kelp; this was mentioned in an earlier blog Sea squirts and sea mats at Ringstead in February. On that occasion, the colony formed a single thin layer on the blade of the seaweed and did not have a solid fleshy shape.

For more information on this marine invertebrate species you can look at the earlier post Star sea squirts – what are they?

I also found the larger sea squirts shown in the photographs below. Here, I am not at all sure what species they are. Quite a lot of the diagnostic features for identification are internal and require dissection of the animal. If anyone reading this post can help out with naming this animal, I would be pleased to hear from them. I have, of course, looked in the text books and suggest that they might be species of Ascidiella.

These sea squirts live as individual animals (unitary) and are not colonial although they may grow in small clusters. Being a lot bigger than the Star Sea Squirts, it’s possible to see the basic structure more clearly. They have a simple ovoid bag shape which is the outer soft test or tunic (one scientific name for these animals is Tunicates).

There are two short tubes or siphons positioned separately. Water that contains small particles goes through one of these tubes (the inhalent siphon) into the central cavity. Here it is seived through the many holes in a complex pharynx that acts as a strainer with many blood vessels. The water is then passed out of the other, exhalent, siphon minus the food particles and oxygen.

If these animals are disturbed, they will contract the muscles suddenly and force the water they contain out of both siphons at the same time – hence their name of sea squirt.

Revision of a post first published 14 June 2010

COPYRIGHT JESSICA WINDER 2011

All rights reserved

I don’t believe I’ve ever seen anything like a sea squirt before.

LikeLike

Hello, Lynn. Sea squirts are an odd sort of animal. Most of them – at least the larger ones – are not very attractive and people find jelly-like things a bit horrid so if they do see these squirts they ignore them or don’t consciously notice them. The smaller colonial squirts like the Star Sea Squirt are colourful and have dainty patterns but you have to look closely to find them. They like to attach to seaweed for example so it is always worth picking up fronds of algae that have washed ashore – and see what is growing on them.

LikeLike