I love Ringstead beach. Ringstead is part of the Jurassic Coast in Dorset, UK, and is just west of Weymouth where some of the sailing events for the 2012 Olympics will be taking place.

It is probably the easiest seashore for me to visit so I go there a lot. Whatever time of year, whatever the weather, it has a lot to offer the walker, the naturalist, and the photographer.

First, it has a good car park very close to the beach. You have to pay but it is worth it. There is a free car park right up on top of the hill but, if you park there, you have a long walk down to the shore at the outset and a long walk uphill on your return when you may be tired. The car park has a little shop that serves refreshments. When the shop is open, so are the toilets which are kept in very good order and clean.

The seashore at Ringstead has different features depending on whether you turn to the left or the right as you go down the ramp to the beach. The shore along the majority of its length comprises yellowy flint stones and shingle that can be quite challenging to walk on. Coarse sands are revealed at the water’s edge.

At the top of the shore (the landward edge) the cliffs display changes in geological structure along their length. The highest point would probably be the chalk of White Nothe at the easternmost edge of the bay.

A lot of the cliff is made up of very sticky grey clay that periodically collapses and slides seawards. Fossils are often washed out of this clay.

At the westernmost edge of Ringstead Bay the cliff consists of limestone in which fossils are also embedded – but different types to those recovered from the clay.

This description is just to give you a general idea of what the beach looks like. I will talk more about the rocks, fossils, and geology of this bay in later posts.

Off shore, usually submerged, there is a series of rocky platforms covered in seaweeds such as kelp and bearing yet more fossils.

On a cold February day in winter, when the wind has been blowing hard onshore and the seas have all been churned up by storms, many things both natural and man-made get cast high up onto the shingle shore. This always includes large pieces of kelp that have become detached from the underwater rock platforms.

If you pause to turn over some of this seaweed, you might discover that it provides a home – a place of attachment – for some very unusual and very small organisms. You will be able to see them because they live in large groups or colonies that are visible to the naked eye.

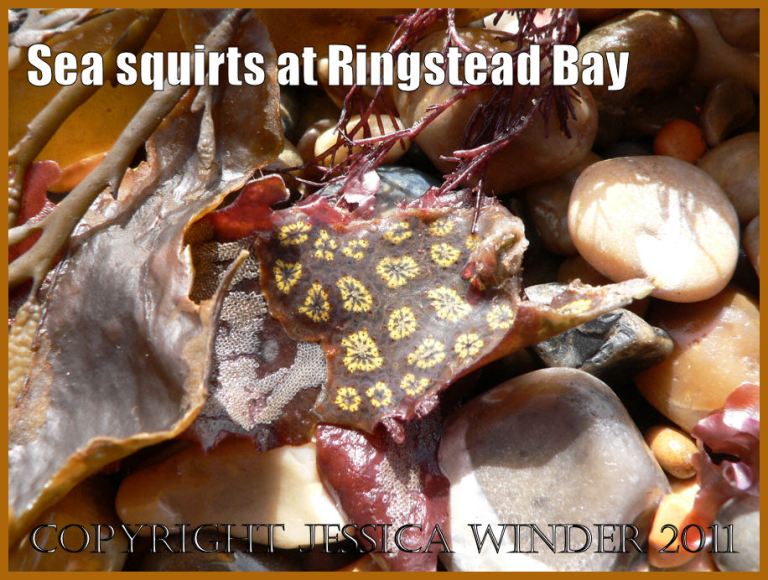

My eye was recently drawn to some kelp with bright yellowy-orange flower-like creatures stuck to it. It is pictured at the top of this post. I had never seen anything like it before. I learned that it was a colonial Star Sea Squirt or Ascidian. Each ‘petal’ of each ‘flower’ is an individual animal. It is called Botryllus schlosseri.

Less spectacular, and far more common, are the sea mats or Bryozoa that form a lace-like colony on seaweeds, shells and stones. An example of such a sea mat is shown in close-up below – again attached to a blade of kelp.

[This is a revision of a post first published 10 February 2009]

COPYRIGHT JESSICA WINDER 2011

All rights reserved

3 Replies to “Sea squirts & sea mats at Ringstead in February”