The Sunday Service sounds poured from Southwark Cathedral as I strolled past. This Christian sanctuary has stood on the South Bank since Saxon times. You would expect such an edifice to be totally grand but its construction reflects its humility as a place for the people. It has always been in the centre of the hustle and bustle of city life, originally in an ‘out of bounds’ part of the city; and now sandwiched between the Borough Market and the old converted spice warehouses on the waterfront.

The exterior of the building is fine enough, with limestone blocks a significant feature. However, most of the outer walls are faced with flint nodules. I had always thought of the inclusion of flint nodules into walls and buildings as a decorative but cheap substitute for stone. I was a little surprised to see flints used so extensively and to such effect in this important building.

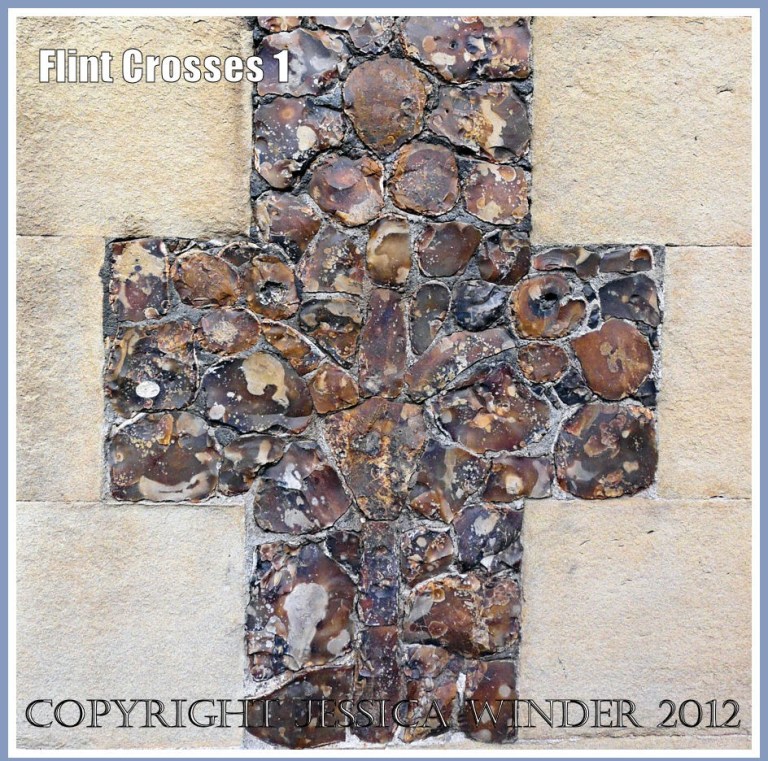

The flints varied a great deal in their natural colour so that in some areas black and grey predominated while in others the stones were more brown. I wondered, in fact, if some of the nodules were in fact chert. The way the nodules had been broken and prepared varied from section to section as well. Sometimes the outer worn powdery coating of the flints was clearly visible and sometimes it was absent or had been removed. Sometimes the nodules were large and the cross-sectional shapes irregular; other times the nodules were smaller and had been worked into a more regular, sub-rectanglar shape. Black flints tended to have larger inclusions in the glassy matrix of the stone and more pronounced conchoidal fractures. The browner flints seemed to feature more numerous and smaller white inclusions and cleaner breaks.

I think these variations might be evidence for the different sources of the basic materials, separate phases of construction work, and different skills levels in the workmen at various times.

The flint crosses shown here are not deliberate architectural features of the building: they are my personal perspective – the photographer’s selective viewpoint. They are areas of dressed flint nodules that fill the spaces between the large rectangular blocks of limestone.

Having said that the ‘crosses’ are not real, I did make an intriguing observation. If you look very closely at the photograph at the top of this post, you will be able to detect that the craftsman has painstakingly included a cross-like design of specially worked smaller flints into this patch. This pattern can only be seen if you are on your knees because it occurs at the very foot of the wall where it meets the path at right angles. It is tempting to speculate that this was a devotional act by workman man who created it.

COPYRIGHT JESSICA WINDER 2012

All Rights Reserved

A fascinating discussion of flint. I like the simple nature of the cross. Have you ever tried to make fire with flint? I tried–not too successfully. It made me respect this stone very much, though.

LikeLike

I haven’t tried to make fire with flint but I know it’s not easy and requires a lot of patience. Do you ever watch the television programmes by Ray Mears who talks about survival techniques? He often travels around the wildernesses of Canada. I have seen him make fire with flint – but he’s an expert.

LikeLike

Jesscia, I have not heard of Ray Mears. But I attended a Tom Brown Jr. wilderness survival school back in the 80s. I think that’s when we tried that fire-making technique. (I was a challenged learner.)

LikeLike

Ray mears is famous over here – if you want to find out more about him, or even enrol for one of his courses, the link is http://www.raymears.com/Ray_Mears/About_Ray_Mears.cfm

LikeLike